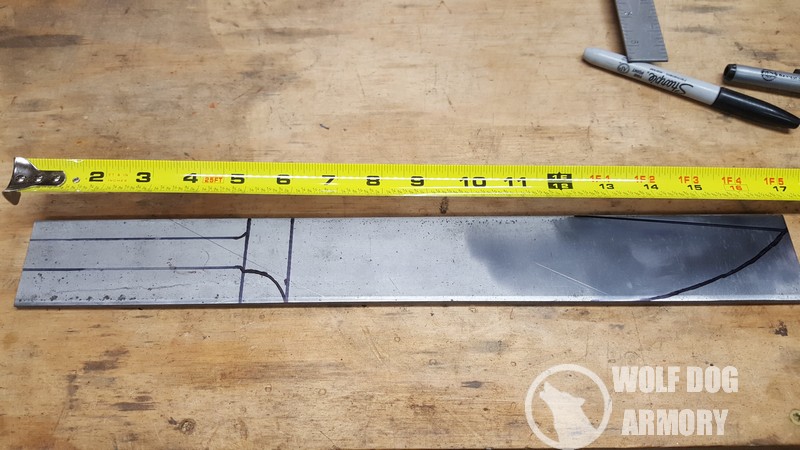

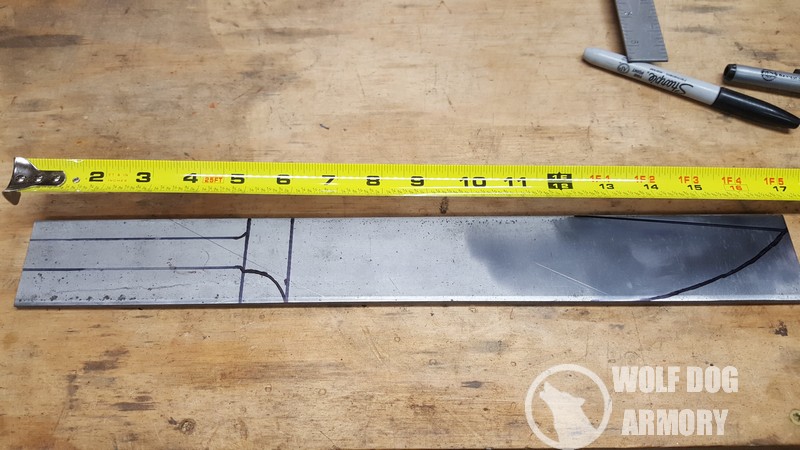

Two of my best friends turned 40 a year apart. I gave Jones the very first Bowie knife I ever made for his 40th last year, so it only seems appropriate that Boyd gets one this year.

Two of my best friends turned 40 a year apart. I gave Jones the very first Bowie knife I ever made for his 40th last year, so it only seems appropriate that Boyd gets one this year.